History of the Alaska Highway Corridor

The Alaska Highway Corridor crosses provincial, territorial, international and cultural boundaries as it winds through northern British Columbia, southern Yukon and up into Alaska. Its geography, geology, flora and fauna encompass arable lands at its south end and sub-Arctic conditions in the north. The human footprint in the Corridor is most clearly evident in the highway itself, in its towns and in protected places, such as Kluane National Park. A closer look reveals that the Corridor has many stories to tell through less obvious human imprints on the landscape, such as places of importance to First Nations, former trading posts along the waterways, old trails and relics from the Second World War era.

The Alaska Highway Corridor crosses provincial, territorial, international and cultural boundaries as it winds through northern British Columbia, southern Yukon and up into Alaska. Its geography, geology, flora and fauna encompass arable lands at its south end and sub-Arctic conditions in the north. The human footprint in the Corridor is most clearly evident in the highway itself, in its towns and in protected places, such as Kluane National Park. A closer look reveals that the Corridor has many stories to tell through less obvious human imprints on the landscape, such as places of importance to First Nations, former trading posts along the waterways, old trails and relics from the Second World War era.

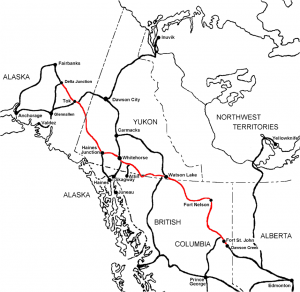

The Corridor’s centrepiece is the Alaska Highway. Over a distance of almost 2,237 km, it crosses five summits ranging from 975 m to 1,280 m to serve residents, tourism, forestry, mining and the oil and gas industry. The highway is divided into three distinct sections. In British Columbia it is known as Highway 97; in the Yukon as Highway 1; and in Alaska as Highway 2. It runs through diverse natural eco-regions, from the Peace River Plains through boreal forests and mountain ranges.

The Highway itself was a significant feat of engineering and was recognized as an event of national historic significance in 1954, and as an International Historic Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers and Canadian Society for Civil Engineering in 1996.

-

The British Columbia section of the Alaska Highway passes through three of British Columbia’s eco-regions: the Boreal Plains (Dawson Creek to south of Fort Nelson), the Taiga Plains (in the Fort Nelson area), and the Northern Boreal Mountains (west of Fort Nelson to the BC-Yukon border).

The Boreal Plains eco-region consists of plateaus and lowlands, mostly forested, with large patches of muskeg. It is crisscrossed by the Peace River tributaries. As the Highway approaches Fort Nelson, it dips into the Taiga Plains eco-region, a lowland plateau bisected by the Liard River watershed and its tributaries, including the Fort Nelson and Petitot rivers. The northern- and westernmost British Columbia section of the Alaska Highway is part of the Northern Boreal Mountain eco-region. This section touches several mountain ranges, as well as valleys and lowlands, including many of the Highway’s iconic vistas.

The Yukon section of the Alaska Highway is part of the Canadian cordilleran region, and the road passes through high plateaus, glacier-fed river valleys, rolling hills and mountainous terrain. Most of the territory is dominated by boreal forest.

-

The archaeological record shows that people have occupied northeastern British Columbia and southern Yukon for at least 11,000 years. Indigenous cultures flourished in the area, spread out and diversified. The Indigenous groups along the corridor from Dawson Creek to the Yukon-Alaska border in rough geographical order are the Dane-Zaa (Beaver), Dene (Slavey), Tse’Kene, Tahltan, Kaska, Tagish, Tlingit, Northern and Southern Tutchone and Upper Tanana peoples. They lived, and continue to live, through hunting and harvesting both before and after contact with Euro-Canadians.

Indigenous people in the corridor entered the fur trade in the late 17th century, and many were firmly integrated into the trade by the late 18th century. Forts and trading posts, such as Fort St. John (1798), Fort Nelson (1805) and Fort Liard (c. 1807), were established on the heels of expeditions by explorers such as Peter Pond (1778) and Alexander Mackenzie (1792). The trading posts in turn opened the way for missionaries, who filtered into the region through trade routes beginning in the early 19th century. Through access to metal tools and implements, rifles, horses, and foodstuffs like flour, tea and sugar, the daily life of Indigenous people changed. Nevertheless, while they certainly embraced the advantages offered by firearms and other technologies, Indigenous people continued to retain and apply their traditional knowledge in daily life, remaining attached to the land and its resources.

Sandy’s first loaf, Klondiker’s camp (near Teslin Lake, BC)

Sandy’s first loaf, Klondiker’s camp (near Teslin Lake, BC)

Credit: H. J. Woodside / Library and Archives Canada / PA-016141. Item No. 770.

The Klondike Gold Rush of 1897-99 also had a significant impact on the lives of Indigenous peoples in northern British Columbia and Yukon. The Gold Rush started after word spread of the discovery of gold by a party of Tagish people and a White prospector. Soon, the region was inundated with tens of thousands of prospectors and hangers-on, most of them American. Although many miners travelled to the gold fields by boat, some chose an overland route via Fort St. John and Fort Nelson. Portions of the Alaska Highway follow the overland gold rush trails, such as the the Kluane Wagon Road blazed by the Jacquot brothers of Burwash Landing.

The Klondike Gold Rush also unleashed a desire to open the Peace River area to settlement and changed the federal government’s position about treaties for areas that are now part of western Alberta and northeastern BC. First to sign Treaty No. 8 were the people around Fort Vermilion and Dunvegan, Alberta in 1899 and Fort St. John, BC in 1900. People from the Prophet River and Fort Nelson areas did not sign until 1910, and Dene signed in groups between 1911 and 1922.

With the end of the Klondike Gold Rush, the population also declined, dramatically. For northeastern British Columbia, in particular, it was as difficult to get around the region as it was to get into and out of it. The Hudson’s Bay Company and British Yukon Navigation Company dominated river travel, and the White Pass and Yukon Railway connected Whitehorse with the pacific via Skagway, Alaska, and the Northern Alberta Railway (NAR) reached as far as Dawson Creek by 1931. Beyond this, however, there were few roads and wagon trails in the region and no reliable transportation connecting the two railroads.

Survey outfit on the move near Fort St. John, BC.

Survey outfit on the move near Fort St. John, BC.

Credit: Canada. Dept. of Mines and Technical Surveys / Library and Archives Canada / PA-020403. Item No. TS 12586.

Northwestern Canada did, however, benefit from developments in air travel during the 1920s and 1930s. Bush pilots like Andy Cruickshank, W. R. “Wop” May, C. H. “Punch” Dickens, and Grant McConachie were responsible for pioneering northern air routes and transporting small-scale developers and prospectors throughout area. However, without proper radio communication facilities, regular weather reports, or in many cases proper landing fields during much of the interwar years, development was slow and air travel often unreliable.

In 1935, the Canadian federal government began surveying possible airfield sites in an attempt to develop a ‘great circle’ aviation route that would stretch across North America to Asia. The studies proposed that the location of the airfields be based on the small landing fields already in use by the bush pilots. In 1939, Canada’s Department of Transport began investing in the proposed airway, and work went into improving the navigational aids and developing larger airfields at Fort Nelson and Watson Lake. Progress was slow, however, and the survey parties were still in the field when war broke out in 1939. Consideration was given to ending the program, but it was decided that, should the United States enter the war, the airfields would prove to have strategic value. With that in mind, the survey work was expedited. By 1940, survey parties had completed detailed engineering surveys and reports for main airports and range station sites, and preliminary surveys for alternate intermediate fields. This work would eventually contribute to the development of the Northwest Staging Route (NWSR).

-

A joint Canadian-American Commission had been formed in 1930s to assess various route proposals for a highway through Canada to Alaska, but the Depression and a general lack of interest in what was perceived to be a road to nowhere put a stop to the effort. Shortly after the start of Second World War, before the US had formally entered the war, but while it had begun supplying aircraft to the allies via Siberia, the US and Canada’s Permanent Joint Board on Defence called for the construction of the Northwest Staging Route (NWSR), a series of airfields stretching from Edmonton, Alberta, through northern British Columbia and the Yukon, to Alaska to facilitate the movement of equipment and men. Based on the ongoing work of the Canadian Department of Transport, the recommendation called for the upgrading of existing airfields in Canada’s northwest, as well as the construction of supplementary landing fields where required. Work was underway by early 1941, funded by Ottawa and undertaken by Canadian contractors. By September of the same year, the NWSR was usable in daylight and good weather.

The attack on Pearl Harbour in December 1941 completely re-altered the position of the US with regard to a road Alaska. With the threat now posed by the Japanese, the Americans became increasingly insistent on the development of a safe overland route from the southern US states to Alaska. Ottawa, while still skeptical, could find no good reason to oppose the request. An agreement was made: the US would pay for the construction, with the sections on Canadian soil to be turned over to Canada six months after the end of the war. Canada, in turn, would provide the right-of-way, waive import duties and other taxes, offer special arrangements for incoming American workers and permit the free use of timber and gravel where required. After decades of discussion, the construction of the Alaska Highway had begun and the spotlight was shining on the Canadian Northwest.

The US Army began construction of the Alaska Highway in March 1942. In a matter of weeks, seven regiments of American engineers (approximately 11,000 men), and 6,000 civilians from Canada and the US, as well as thousands of pieces of equipment, arrived in Canada’s northwest to undertake one of the most tremendous engineering achievements in the world. By October 1942, a 2451-km rough ‘pioneer’ road, beginning at the railhead in Dawson Creek, BC and ending in Fairbanks, Alaska, was passable and in use for supply purposes. The pioneer road was officially opened 20 November 1942, with a ceremony at Mile 1061 known as ‘Soldiers Summit’. Responsibility for the construction of the final road fell to the US Public Roads Administration (PRA) and was undertaken by five main contractors who were responsible for an additional seventy-nine Canadian and American companies. Initially referred to as the Alcan Highway, on 19 July 1943, Canada and the US exchanged diplomatic notes formally naming it the Alaska Highway.

The PRA’s work lasted into November 1943, and improvement works shortened the highway by approximately 95 miles (153 km). Maintenance of the Alaska Highway fell to the US Army for the duration of the war. The completed Alaska Highway included 133 bridges, five summits between 975 m to 1,280 m and permitted speeds from 65 to 80 km an hour.

Construction of the Alaska Highway initiated a wide array of related projects, known as the Northwest Defence Projects, which spanned over one million square miles of northwestern Canada and Alaska. In addition to the NWSR, which the highway had been designed to support, the region also saw the construction of an oilfield, refinery and pipeline system known as Canol. It also saw an extensive network of telephone lines and temporary landing strips. An additional road, linking the Alaska Highway with the port at Haines, Alaska, was also constructed in 1943 as an alternative to the White Pass and Yukon Route railway.

-

Two Army officials shake hands at the transfer ceremony on April 3, 1946.

Two Army officials shake hands at the transfer ceremony on April 3, 1946.

Credit: South Peace Historical Society Archives. Resource ID: 1274.

Canada took over its sections of the Alaska Highway six months after the end of the war on 1 April 1946. Responsibility for maintaining the Highway now fell to the Canadian Army, and in turn the Northwest Highway System (NWHS) wing of the Royal Canadian Engineers. With the transfer of the Highway to the military rather than the local governments, strict restrictions on travel were put in place over the following years. Travellers needed to obtain permits to use the highway and were required to take a long list of supplies and equipment with them, given the still rough conditions.

When the US Army departed in 1946, it left a rough, winding road that connected a few small communities, but the era of traders and bush pilots controlling transportation routes was over. By 1964, when the Alaska Highway was transferred to the Canadian Department of Public Works, the NWHS had built more than 100 new bridges.

The Northwest Defence Projects, which included the Alaska Highway, the Canol pipeline, the NWSR and associated airfields, additional roads, and a telephone system, pushed the Alaska Highway Corridor toward a more integrated economy with the south. The new highway made it possible for local people to drive south and for southerners to head north and experience Canada’s northwest. For those who were adventurous enough, the highway also offered an opportunity to experience the isolation, vast wilderness and beauty of the north. Over the following years, technological developments resulted in improvements not only to the Alaska Highway, but to the communication lines, airfields and connecting roads in the region and tourism slowly began to expand. Tourist traffic increased from 18,600 in 1948 to almost 50,000 three years later; today the Alaska Highway hosts over 300,000 visitors annually.

-

The Alaska Highway affected settlement patterns in the region. Prior to its construction, northern British Columbia and the Yukon were sparsely populated and the majority of the Alaskan population lived in coastal communities. In northern British Columbia and the Yukon, communities sprang up in response to the road and the services and opportunities it offered. For many, the Alaska Highway would become their ‘main street’. As the headway for the Alaska Highway, Dawson Creek is a prime example of a community transformed from a small prairie town to a regional centre.

In addition, the sustainable access provided by the Highway allowed for the integration of the region into the national economy through both renewable and non-renewable resource development. Geologists and prospectors followed right behind construction crews. Places like Taylor, Fort Nelson and Fort St. John in BC, originally boosted by their placement along the Alaska Highway and the NWSR, again benefitted from the discovery of natural gas fields and oil in the post-war years.

In Yukon, the highway also supported mining production and transformed transportation. The Alaska Highway’s construction and the subsequent construction of all-weather roads to Mayo and Dawson City put an end to the sternwheeler era and over a half century of the Yukon River serving as the territory’s main transport corridor. The decision to bypass Dawson, once the most important centre northwest of Edmonton, Alberta, resulted in the community’s slow decline, and Whitehorse, in turn, grew as a metropolitan city. In 1953, Yukon’s capital was officially moved from Dawson City to Whitehorse.

Both the impacts felt from the influx of men for the construction of the highway, and the highway’s subsequent success in opening up Canada’s North justified the setting aside of many areas for recreation and conservation. The Liard River Reserve evolved into three provincial parks – Liard River Hotsprings, Muncho Lake and Stone Mountain – and Kluane National Park Reserve was established in 1972.

-

The construction of the Alaska Highway had a major, although geographically varied, impact on the lives of Indigenous people in the region. Men from First Nations communities were only marginally involved in the construction itself, generally working as guides or labourers. They knew the country, its climate and its people. Indigenous women were also hired to do laundry, make and repair clothing, work in restaurants and assist in office work.

A First Nations man, Field Johnson, his horse and his fully loaded pack dog posing for the photographer. A US service man is in the background.

A First Nations man, Field Johnson, his horse and his fully loaded pack dog posing for the photographer. A US service man is in the background.

Credit: Yukon Archives, Robert Hays fonds, #5706.

The arrival of the construction crews increased the exposure of Indigenous people to infectious diseases, such as measles, influenza, dysentery, whooping cough, mumps, and meningitis, with devastating consequences to the population. Infants and children were especially vulnerable. The highway’s construction also had an environmental impact, as animal patterns were disrupted. Soldiers were known to use wildlife for target practice, and an increased demand for meat for construction crews and cities, depleted much of the big game.

The story of the short-term and long-term impacts of the Alaska Highway are made more complex because other outside factors changed life in Canada’s north in the post-war period as well. Family allowance became available in the 1950s, but families were told that children had to be registered and attending school, which drew people off the land. Young people moved to larger communities to go to school, receive training and find employment. While residential schools were part of the pre-highway history for First Nations in BC and Yukon, the opening of the Alaska Highway made it easier for children to be taken away from their communities to attend the schools.

The construction of the Alaska Highway served as a powerful means of communication and transportation, ending the relative isolation of the region and changing the economic and social landscape permanently. Today, Indigenous people are part of the cultural, social and economic fabric of the corridor, while also retaining close connections to the land and its bounties. They are involved in construction, resource development, tourism, business development and cultural production throughout Canada’s North.

As an ensemble, the Alaska Highway Corridor is more than a remarkable feat of engineering; it is also an enduring landmark in the history and identity of the region and Canada. The corridor sustained communities long before the fur trade, infrastructure, permanent settlements, tourism, and resource development altered the region’s transportation networks, economy and environment. Dramatic changes were enabled and accelerated by the construction of the Alaska Highway, and the impacts of the Highway, both positive and negative, have had a lasting effect on Canada’s northwest.

-

Learning More about the History of the Alaska Highway Corridor

While not a comprehensive list, the following websites and books are valuable to understanding the history of Canada’s northwest and the Alaska Highway.

Online:

Ordinary Men Build A Legendary Road: 93rd Engineers & the ALCAN Highway by Christine McClure

The Alaska Highway: A Yukon Perspective by the Yukon Archives

The Alaska Highway: Background to Decision by Richard G. Bucksar

Building the Alaska Highway by PBS

History is Where you Stand: A History of the Peace by the South Peace Historical Society

US Army Corps of Engineers: A Brief History by the US Army Corps of Engineers

US Army in World War Two: Special Studies – Military Relations Between the U. S. & Canada by Stanley W. Dzuiban

The Year of the Alaska Highway: 1942 by Katherine Koller

Carlson, Roy L., and Luke R. Dalla Bona. Early Human Occupation in British Columbia. Vancouver: UBC Press, 1996.

Coates, Ken and William R. Morrison. The Alaska Highway in World War II: The U.S. Army of Occupation in Canada’s Northwest. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1992.

Coates, Ken, Ed. The Alaska Highway: Papers of the 40th Anniversary Symposium. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1985.

Coates, Ken. North to Alaska! Fifty Years on the World’s Most Remarkable Highway. Alaska: University of Alaska Press, 1991.

Crowe, Keith J. A History of the Original Peoples of Northern Canada. Arctic Institute of North America. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1974.

Cruikshank, Julie. Do Glaciers Listen?: Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters, and Social Imagination. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2005.

Dickason, Olive Patricia. Canada’s First Nations: A History of Founding Peoples from Earliest Times. Toronto: McClelland and Stewart, 1992.

Duff, Wilson. The Indian History of British Columbia: The Impact of the White Man. Victoria: Royal BC Museum, 1997.

Gates, Michael. Dalton’s Gold Rush Trail: Exploring the Route of the Klondike Cattle Drives. Whitehorse, YT: Lost Moose, 2012.

Hilborn, James D. Dusters and Gushers: The Canadian Oil and Gas Industry. Toronto: Pitt Publishing Company Limited, 1968.

Innis, Harold A. The Fur Trade in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1999.

Jenness, Diamond. The Indians of Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1977.

Johnson, Leslie Main. Trail of story, traveller’s path reflections on ethnoecology and landscape. Edmonton: AU Press, 2010.

Helm, June, Ed., Handbook of North American Indians Volume 6, Subarctic. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1981.

Madill, Dennis F. K. Treaty Research Report: Treaty Eight. Ottawa-Hull: Treaties and Historical Research Centre, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 1986.

McAllister, Bruce and Peter Corley-Smith. Wings Over the Alaska Highway. Boulder, CO: Roundup Press, 2001.

McCellan, Catherine. My Old People Say: An Ethnographic Survey of Southern Yukon Territory, Part 2. Hull, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization, 2001.

McClellan, Catharine, and Lucie Birckel. Part of the Land, Part of the Water: A History of the Yukon Indians. Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1987.

McGrath, T. M. History of Canadian Airports. Canada: Lugus Publications in Cooperation with Transport Canada and the Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Supply and Services Canada, 1992.

Menzies, Don. The Alaska Highway: A Saga of the North. Edmonton: S. Douglas, [1943].

Nadasdy, Paul. Hunters and Bureaucrats Power, Knowledge, and Aboriginal-State Relations in the Southwest Yukon. Vancouver, BC: UBC Press, 2003.

Neufeld, David. “Kluane National Park Reserve, 1923-1974: Modernity and Pluralism.” In A Century of Parks Canada, 1911-1921, edited by Claire Elizabeth Campbell. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2011.

Ray, Arthur J. An Illustrated History of Canada’s Native Peoples. Third edition. Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2010.

Ray, Arthur J. The Canadian Fur Trade in the Industrial Age. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990.

Sherwood, Jay. In the Shadow of the Great War: The Milligan and Hart Explorations of Northeastern British Columbia 1913-1914. Victoria, BC: Royal BC Museum, 2013.

Stone, Ted. Alaska and Yukon History Along the Highway: A Traveler’s Guide to the Fascinating Facts, Intriguing Incidents and Lively Legends in Alaska’s and Yukon’s Past, History Along the Highway. Red Deer: Red Deer College Press, 1997.

Timoney, Kevin P. The Peace-Athabasca Delta: Portrait of a Dynamic Ecosystem. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2013.

Tubman, Allison. The McDonalds: The Lives & Legends of a Kaska Dena Family. Canada: Backyard Productions, 2014.

Twichell, Heath. Northwest Epic: The Building of the Alaska Highway. St. Martin’s Press, 1992.

Wonders, William C. Alaska Highway Explorer: Place Names Along the Adventure Road. Victoria, BC: Horsdal & Schubart Publishers, 1994.

Wright, Allen A. Prelude to Bonanza: The Discovery and Exploration of the Yukon. Sidney, BC: Gray’s Publishing Ltd., 1976.

Wright, Chris. Air Route to the Klondike: An Aviation History. Air Pilot Navigator: Volume Three. Victoria: Creekside Publications, 2006.